War in Europe?

Ukraine and the Threat of Wildfire

By SPIEGEL Staff

Following the apparent failure of the Geneva agreements, the inconceivable suddenly seems possible: the invasion of eastern Ukraine by the Russian army. Fears are growing in the West of the breakout of a new war in Europe.

When he was deployed as a soldier in the Ukraine, in 1943, Fausten was struck by grenade shrapnel in the hollow of his knee, just outside Kiev, and lost his right leg. The German presence in Ukraine at the time was, of course, part of the German invasion of the Soviet Union. But, even so, Fausten didn't think he would ever again witness scenes from Ukraine hinting at the potential outbreak of war.

For anyone watching the news, these recent images, and the links between them, are hard to ignore. In eastern Ukraine, government troops could be seen battling separatists; burning barricades gave the impression of an impending civil war. On Wednesday, Russian long-range bombers entered into Dutch airspace -- it wasn't the first time something like that had happened, but now it felt like a warning to the West. Don't be so sure of yourselves, the message seemed to be, conjuring up the possibility of a larger war.

'A Phase of Escalation'

Many Europeans are currently rattled by that very possibility -- the frightening chance that a civil war in Ukraine could expand like brushfire into a war between Russia and NATO. Hopes that Russian President Vladimir Putin would limit his actions to the Crimean peninsula have proved to be illusory -- he is now grasping at eastern Ukraine and continues to make the West look foolish. Efforts at diplomacy have so far failed and Putin appears to have no fear of the economic losses that Western sanctions could bring. As of last week, the lunacy of a war is no longer inconceivable.

On Friday, leading Western politicians joined up in a rare configuration, the so-called Quint. The leaders of Germany, France, Britain, Italy and the United States linked up via conference call, an event that hasn't happened since the run-up to the air strikes in Libya in 2011 and the peak of the euro crisis in 2012 -- both serious crises.

Germany's assessment of the situation has changed dramatically over the course of just seven days. Only a week ago, the German government had been confident that the agreements reached in Geneva to defuse the crisis would bear fruit and that de-escalation had already begun. Now government sources in Berlin -- who make increasing use of alarming vocabulary -- warn that we have returned to a "phase of escalation."

Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk spoke of a "worst-case scenario" that now appears possible, including civil war and waves of refugees. Ukrainian interim Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk has even gone so far as to claim that "Russia wants to start a Third World War." (Though, of course, Yatsenyuk also wants to instill a sense of panic in the West so it will come to the aid of his country.)

There may not be reason to panic, but there are certainly reasons for alarm. After 20 years in which it was almost unimaginable, it seems like a major war in Europe, with shots potentially being fired between Russia and NATO, is once again a possibility.

"If the wrong decisions are made now, they could nullify decades of work furthering the freedom and security of Europe," German Foreign Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier of the center-left Social Democratic Party (SPD) told SPIEGEL in an interview. Norbert Röttgen, a member of Angela Merkel's conservative Christian Democratic Union (CDU) party and the chairman of the Foreign Affairs Committee in the German parliament, said, "The situation is getting increasingly threatening." His counterpart in the European Parliament, Elmar Brok of the CDU, also warned, "There is a danger of war, and that's why we now need to get very serious about working on a diplomatic solution."

'Against the Law and without Justification'

Friday's events demonstrated just how quickly a country can be pulled into this conflict. That's when pro-Russian separatists seized control of a bus carrying military observers with the Office of Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) and detained the officials. As of Tuesday, seven observers were still in detention, including four Germans -- three members of the Bundeswehr armed forces and one interpreter.

Member of proRussian forces guards a checkpoint near the town of Slaviansk in eastern UA May 2, 2014

The same day, Vyacheslav Ponomaryov, the de facto mayor of Slavyansk, told the Interfax news agency that no talks would be held on the detained observers, whom he has referred to as "prisoners of war," if sanctions against rebel leaders remain in place. On Monday, Chancellor Angela Merkel's spokesman, Steffen Seibert, condemned the detentions, describing them as "against the law and without justification." He called for the detainees to be released, "immediately, unconditionally and unharmed." German officials have also asked the Russian government "to act publicly and internally for their release."

The irony that these developments and this new threat of war comes in 2014 -- the 100th anniversary of the outbreak of World War I and the 75th of the start of World War II -- has not been lost on anyone. For years, a thinking had prevailed on the Continent that Europe had liberated itself from the burdens of its history and that it had become a global role model with its politics of reconciliation. But the Ukraine crisis demonstrates that this is no longer the case.

'All Signs Point to an Armed Conflict'

The question now becomes: How far will events in Ukraine go? Fausten, the retired school principal, says he doesn't believe they will lead to war. "The Ukrainians and Russians are still grappling with the aftermath of the world wars," he says. "I can't imagine that the Russians will allow this to come to that."

Others in Germany are beginning to fear the worst. Pastor Heribert Dölle, 57, of the Catholic Church parish in Düsseldorf's Derendorf and Pempelfort districts, has been gathering other impressions. One of the churches in the parish is shared by Düsseldorf's Catholics and Ukrainian Christians. "It feels almost as if we are experiencing the conflict right at our front doors," Dölle says. "We know each other and fears about what is happening right now in Russia and Ukraine are rising."

In Berlin, Christian Mengel is just one of the droves of tourists who continued to make their way to the capital city's dramatic Soviet War Memorial. "All signs point to an armed conflict, but I do not believe that NATO will intervene and I certainly hope they do not," he says. Visitor Hans Pflanz echoes his sentiment. "I'm afraid that this conflict could expand into an international crisis," he says. "I think our politicians don't understand the Russians' intentions and motives." He says he would prefer the West to remain acquiescent to Russia-- an opinion shared by the majority of Germans, according to pollsters.

Germany Harbors Unique Fear of War

Since 1945, Germany has been been particularly afflicted by worries about wars. As in other countries, millions of Germans died on the fronts and in the cities during the two world wars, but here, an additional factor has weighed heavily: guilt. Even today, Germans remain uncertain whether the Prussian militarism and unconscionable obedience that influenced the country during those wars has been banished entirely or whether it might rear its ugly head again in a time of crisis. Postwar Germans have and continue to long for peace, partly to remain so with themselves.

Germany's fear of war has provided the country with a fertile soil for pacifism. Over the past decades, the German peace movement has fought against the arming of the German Air Force with nuclear weapons as well as plans for the stationing of middle-range missiles by NATO in the 1980s.

The protests against the Vietnam War in the late 1960s and early 1970s and again during the first Iraq War in 1991 were always infused with some anti-American sentiment. The peace movement's fear of war led it to consistently demand peace from NATO and the West, but when it came to the Soviet Union, its efforts tended to range from friendly to indifferent.

Since the 1970s, peace marches have taken place during the Easter Holiday in Germany and other parts of Europe. It's an important annual event for pacifists, but this year only a few thousand people turned out for them in Germany: Neither Putin's aggressions nor NATO's reactions to them seem to have done much to awaken the slumbering peace movement. Nevertheless, the pacifist mentality is still alive and well. "War is crap. I'd rather stuff flowers into rifle barrels," German film and theater director Leander Haussmann says of the current crisis.

Three-Quarters of Germans Oppose NATO Intervention

Three-quarters of all Germans oppose a military intervention by NATO in the Ukraine crisis and one-third say they can sympathize with Putin's decision to annex Crimea. These sentiments, it seems, stem at least in part from Germans' latent fear of war.

Prominent German political scientist Herfried Münkler uses his theories of "heroic" and "postheroic" societies to describe the phenomenon. At the recent Petersburg Dialogue in Leipzig -- an important forum between Germany and Russia that has brought together representatives of the worlds of politics, culture and business since 2001 -- Münkler said this "postheroism" is essentially an expression of prosperity, the German daily Die Tageszeitung reported. Those who have it good don't want to jeopardize their good fortune.

Münkler argues that, as a rule of thumb, there's an ideal of "heroism of masculinity" in poorer and less developed counties in which notions of war and defense of the homeland are idealized. In "postheroic" societies, however, which tend to be well-developed and prosperous, war is deemed to be aberrant. According to the newspaper, he argued that Eastern Europe isn't prosperous enough to discourage young men from this idea of heroism. Indeed, politicians can often profit if they are able to tap these emotions. When it comes to Putin's policies, he argues, this heroism aspect makes the situation unpredictable. "Dynamics are being toyed with that, at some point, will no longer be controllable," he said.

That sense of heroism was recently on display on Maidan Square in Kiev, where, five months ago. the current crisis began. There, three men stood in front of a barrel on a sunny spring day and used their powerful voices to sing an impassioned song about the "Cossacks' blood-bought glory" and the "Moskaly," a pejorative for Russians. "When the Moskaly cross the border, we'll finish them off," says Dmytro, a 30-year-old whose head has been shaved clean, save for a small tail. He says an invasion by the Russians is only a matter of time, but that his people will be undefeatable if it comes to war. "A Ukrainian with a tail on his head like mine and a weapon in his hand will sit behind every bush," he says.

Although most people would argue it's a good thing that postwar Germany has overcome this kind of "masculine" thinking, some might argue that the country has swung too far toward the opposite end of the spectrum. Germany still plays a major role in global politics, including with the Ukrainians and the Russians, but it is far more timid than some of its most important Western allies.

The French are less anxious about military conflict than the Germans, largely because they have often deployed their military in Africa and thus gotten used to war. The French, just like the British, also feel they are in a good position to defend themselves because they possess nuclear weapons. The Germans, on the other hand, are reliant on others' such weapons, which further feeds domestic sensitivities. They have a particularly tough time lending their full trust to the Americans, whom they have repeatedly perceived to be acting imperialistically -- as a result, many Germans worry the US might drag them into its dirty business.

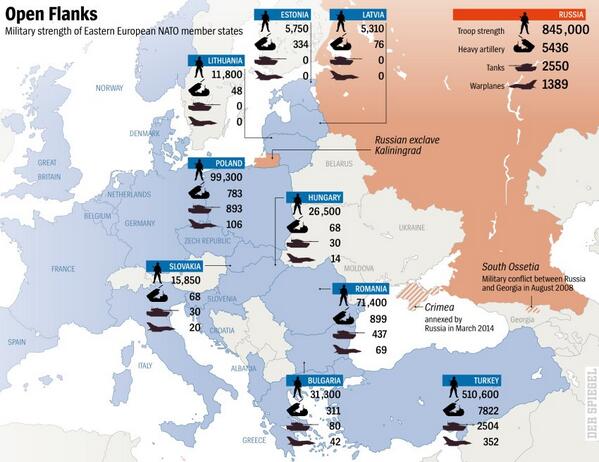

So far, much of the escalation in this crisis has happened in the diplomatic sphere, with cancelled meetings and threats of sanctions, but there have also been military movements. Last week, the US said it would deploy 600 soldiers to Poland and the Baltic states for exercises, a move it made without NATO's preemptive approval, and the Russians are now conducting maneuvers right on the other side of the Ukrainian border. Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov warned last week, "An attack against Russians is an attack against Russia." Those are the kinds of comments that could later be used to justify an intervention. They also subtly demonstrate how the threat of war is growing.

'Security Is Threatened'

These days, Germany is in a much better position than during the Cold War. Back then, the two German nations were frontline states and had the potential to become the site of the first battles if a conventional war broke out. Today, that role would most likely fall to the Ukrainians, the Poles and the Baltic states.

German Air Force Eurofighter over Lithuania as part of Nato protection of the Baltic States

It's a role that pleases few in the East. "Basically, there is a feeling in Poland that, for the first time since 1989, our security is threatened," says Polish diplomat Janusz Reiter, who served as ambassador to Germany from 1990 to 1995. Reiter says it's not so much a fear of being "affected by an imminent military threat," as the return of a feeling that Poland is living in the shadow of its giant neighbor -- one that is prepared to use force to alter Europe's borders or plunge a country like Ukraine into a civil war.

Countries in the region have plenty of unpleasant memories of when Russia was part of the Soviet Union. Lithuanians, Latvians and Estonians experienced the Soviet Union as an occupying force during World War II. In 1956, Soviet troops crushed the Hungarian uprising. Again in 1968, it was the Soviet Union's tanks that quashed the Prague Spring. Given that history, these countries have considerable difficulty overcoming the suspicion that Moscow is seeking to reclaim its former greatness.

The Baltic states are also home to sizeable populations of ethnic Russians. Six percent of the population of Lithuania is Russian; in Latvia and Estonia, the minority represents more than a quarter of the total population. So far, the Baltic Russians have remained loyal to their countries -- there aren't any splinter parties calling for annexation by Russia.

Nevertheless, governments in the region worry that their Russian populations could allow themselves to get pulled into the conflict. The governments of Latvia and Lithuania have shut down transmitting stations for the Russian-language broadcaster Russia RTR because it is sponsored by Moscow. Plans are afoot now to establish an independent Russian-language station for the region.

Parallels to Conflicts in Former Yugoslavia?

Czech President Milos Zeman said last week that he sees a bloody scenario brewing in Ukraine similar to the conflicts in the former Yugoslavia during the 1990s. Both the Czech Republic and Slovakia assume that thousands of refugees will flee if the violence escalates.

As terrible as the Yugoslav wars were, they at least remained regional in scope, partly because the Russians refrained from intervening militarily and because the Americans also force to ensure that the fighting ended. This time the situation is more complicated. The Russians are engaged militarily, and if the Americans attacked, it would become a war between the superpower and a major power.

At the same time, it's unlikely the Americans will intervene. After 10 years of fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan, the US has become weary of war. Many Americans are also only marginally interested in Ukraine and -- despite warnings from members of the Republican Party who are busy conjuring up the return of the Cold War -- have lost the sense that Russia poses any kind of immediate threat. In the American media, the Ukraine crisis is just one story among many. CNN recently gave heavier play to the search for the missing Malaysia Airlines plane.

Despite lukewarm interest on the part of most Americans, the Ukraine crisis represents a true political dilemma for President Obama. He views his own country as unprepared to make sacrifices for Ukraine, but with a desire for a strong president who can be tough in global flare-ups.

Among those demanding a firmer approach is former Republican presidential candidate John McCain. He bemoans that Obama is gambling away the United States' reputation as the world's last superpower. "This administration, I have never seen anything like it in my life," McCain said in an interview last week with the Wall Street Journal. "It's passive," he criticized. "Vladimir Putin understands peace through strength and nothing else. And so far we've made a lot of threats and done almost nothing."

The most likely scenario is a maintenance of the status quo -- in which Ukraine slips into a state of civil war that fuels Russia, leading the West to respond with economic sanctions, but little, if anything, more.

That scenario might be more palatable for many in the West, since it would spare them from going to war. But it wouldn't spare them moral culpability if bloodshed occurred on European soil.

Memories of World War I

Perhaps the most reasonable words at the moment are those coming from Horst Seehofer, the head of the Christian Social Union, the Bavarian sister party to Chancellor Angela Merkel's conservatives. "We should stick to our double strategy," he says. "We should continue to maintain diplomatic contacts with Russia, but we should also be prepared for another round of sanctions if necessary."

The prospect of civil war in Ukraine is also fraught with the danger that the conflict could explode and spill across the borders of its Western neighbors. Then Article 5 of the NATO charter would have to be invoked, requiring all members to come to the defense of a member under attack. By then, at the very latest, Germany would also be pulled in to the conflict.

The head of Germany's Protestant Church even offers words addressing such extreme scenarios. "With threats of war, flexing of military muscles and increasingly aggressive rhetoric, Christians around the world are viewing this conflict with the deepest concern," says Nikolaus Schneider, chairman of the Evangelical Church in Germany (EKG).

"As the Protestant Church in Germany, in 2014," he says, "we are thinking very intensely back to 1914" -- the year World War I broke out.

BY JÜRGEN DAHLKAMP, MORITZ GATHMANN, MARC HUJER, DIRK KURBJUWEIT, PAUL MIDDELHOFF, PETER MÜLLER, JAN PUHL, BARBARA SCHMID AND PETER WENSIERSKI

No comments:

Post a Comment