DONETSK, Ukraine -- The sight of bodies fallen from the sky and strewn across the fields outside the village of Hrabovo will stay with those who saw it for a long time.

The image of a Russian thug taking a dead man’s wedding ring, evoked with dignity and disgust by Dutch foreign minister Frans Timmermans in a speech to the UN Security Council, is a powerful one.

At least one picture has emerged which appeared to show a ring being taken by a rebel from a body at the crash site

The missile attack on Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 by Russian-backed rebels in eastern Ukraine killed 298 people and shocked the world.

How it might affect the outcome of the war into which the wreckage fell, though, remains to be seen.

On July 21st, four days after the Boeing 777 was brought down, the human remains that had been piled into grey refrigerated railway cars near the crash site finally left for Kharkiv, from where they were flown to the Netherlands.

The separatist forces at the scene numbered the bodies at 282; Dutch experts put the number closer to 200.

In the small hours of the next morning the plane’s black boxes were handed over to Malaysian representatives in a bizarrely formal ceremony in the rebels’ administration building in Donetsk.

One Dutch expert praised the local teams that had taken part in the recovery as doing “a hell of a job in a hell of a place”.

But the obstruction and intimidation by rebel forces that kept investigators and other responders from the site served only to deepen anger in the rest of the world.

Among the rebel rank and file, and in most places where news outlets are controlled by Russia, there is a widespread belief that MH17 was brought down by Ukrainian aircraft, perhaps as a way of eliciting further Western support by blaming Russia, perhaps because they mistook it for an aircraft carrying the Russian president, Vladimir Putin.

Local people in eastern Ukraine, used to seeing rebels with outdated weapons on the streets, don’t think them capable of bringing down an airliner.

In the rest of the world, though, the evidence seems, if circumstantial, incontrovertible.

“We have just shot down a plane”

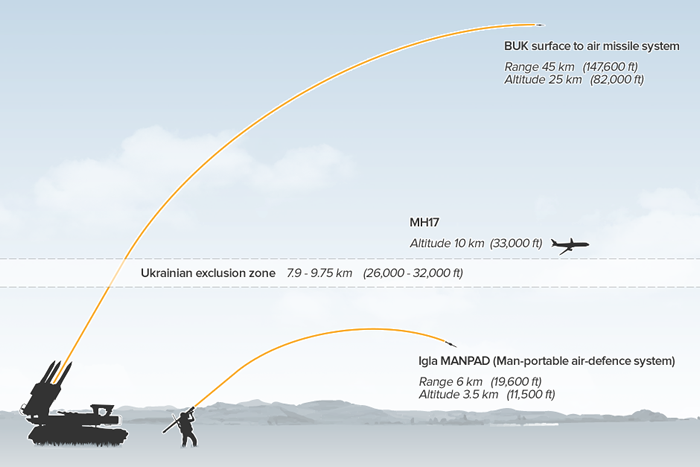

The flight was cruising at 10,000 metres (33,000 feet), an altitude at which only a sophisticated surface-to-air missile system or another aircraft would be able to hit it.

The only such systems known to be in the area are Buk missiles which are under the control of the rebels.

On July 17th a BUK missile launcher was seen on various social media moving towards Snizhne, about 80km (50mi) from the rebel stronghold of Donetsk and close to where the aircraft was shot down.

A Buk missile system moving through the town of Snizhne.July 17th 2014.

America says a missile was launched from the area just before the aircraft was destroyed.

In a phone call made half an hour after the remains of MH17 hit the ground Igor Bezler, a separatist leader, told a Russian intelligence officer “we have just shot down a plane”.

That call and others were intercepted and made public by Ukrainian intelligence; the American embassy in Kiev subsequently issued a statement confirming the authenticity of the transcripts.

This evidence led Barack Obama and many other Western leaders to place the blame firmly on Putin, the rebels’ reckless sponsor and, in all likelihood, the supplier of the missile.

That condemnation added to the pressure felt when the European Union’s foreign ministers met in Brussels on July 22nd to consider its response.

The EU’s previous unwillingness to propose sanctions that might impose real costs on the members looked more spineless than ever.

The Netherlands, which lost 193 citizens in the attack, including the eminent AIDS researcher Joep Lange, supported a toughened line; Italy, often an obstacle to tightening sanctions, made no attempt to block such moves.

Several ministers spoke of a turning point in relations with Russia.

The communiqué they issued said they would “accelerate the preparation of targeted measures” which had been agreed at an earlier summit, increasing the number of people and entities “materially or financially supporting” Russia’s policy of destabilising eastern Ukraine that will be subject to travel bans and the freezing of assets.

The ministers said they would act by the end of the month.

Such incremental measures amount to expanding so-called “phase two” sanctions against Russia, bringing Europe closer in line with America.

Of greater importance is that the communiqué raised the prospect of the EU moving to “phase three” sanctions, which are aimed at whole economic sectors, if Russia fails to meet demands that it use its influence with Ukrainian rebels to ensure the crash site is preserved intact for investigation and that the flow of weapons and fighters from its territory into Ukraine be halted.

From Rostov, with BUKs

That the Russians are supplying the rebels is not open to doubt.

Indeed, a recent increase in the flow of supplies seems to have set the scene for the tragedy.

On July 1st Petro Poroshenko, Ukraine’s president, brought to an end a ceasefire in the east of the country which had lasted for ten days and which, he claimed, the rebels had broken 100 times.

He was betting that Ukraine’s armed forces, their morale boosted through the expedient of newly regular pay as well as training and better maintenance for their equipment, could take on and defeat 10,000-15,000 rebels armed mainly with light weapons and a few elderly tanks.

On July 5th, after an artillery bombardment, Ukrainian forces hoisted their blue and yellow flag over the strategically important town of Slavyansk, which had been the military headquarters of the insurrection.

Air power was a big part of the success.

Though the rebels had shot down several planes and helicopters using Strela-2 shoulder-fired missiles, they were impotent against anything flying above 2,000 metros (6,500 feet).

The separatists’ military leader, Igor Girkin (aka Igor Strelkov), a former or possibly current Russian intelligence officer, pleaded with Putin for help in turning the tide.

Although Putin would not send the troops that Girkin wanted, he was willing to provide him with enough weapons and assistance to stay in the game.

Since late June small convoys of Russian heavy weapons had been flowing into the Luhansk region of Ukraine from a deployment and training site set up near Rostov by the separatists’ Russian military helpers, according to Western intelligence sources.

On July 13th, at about the same time that Putin was sitting down to watch the World Cup final with Angela Merkel, the German chancellor, American sources say that a much bigger convoy of around 150 vehicles made the journey.

It is said to have included tanks, artillery, Grad rocket launchers, armoured personnel carriers and Buk missile systems.

Russia flatly denies having sent any such missiles.

Whether it was a missile delivered by that convoy that brought down MH17 is unknown.

There were reports in late June that the rebels had captured such missiles from the Ukrainians, though the Ukrainians deny this and it may well have been deliberate Russian misinformation.

But successful attacks on aircraft started straight after the convoy’s arrival.

On July 14th a Ukrainian military cargo plane with eight people on board was brought down a few kilometres from the Russian border.

The aircraft was flying at 6,500 metros (21,000 feet), well beyond the range of shoulder-fired missiles.

The following day a Ukrainian Su-25, a ground-attack fighter that has been used extensively against rebel positions, was hit.

On July 16th another Su-25 suffered a missile strike but managed to land.

It may be significant that the pictures showing the BUK missile launcher that shot down MH17 on its way to Chernukhino show it travelling alone.

In normal operations the launcher would be accompanied by separate vehicles carrying radar and control facilities.

Without these the system would have lacked, among other things, an ability to sense the transponders that civilian aircraft carry.

Assuming that the crew wanted to shoot down another Ukrainian military transport, this lack would have made it easier for them accidentally to hit a passenger jet flying both higher and faster than any such target.

The show must go on

That it was indeed a mistake is hard to doubt, not least because it clearly put Putin on the defensive.

In the days after the attack he threw himself into a frenzy of diplomatic and public activity, talking repeatedly to Mrs Merkel and Mark Rutte, the Dutch prime minister, as well as to the leaders of Australia, Britain and France.

On July 21st he gave an address to the nation unremarkable in every way other than its timing; it was broadcast in the middle of the Moscow night, which means just before the previous evening’s prime time on America’s east coast.

Russian President Vladimir Putin speaks during a recording of nationwide TV address, early Monday, July 21

Having asked for concessions it did not receive, Russia still backed the Security Council’s resolution calling for a full investigation and for those responsible to be held to account, a resolution which accordingly passed unanimously.

For all his anti-Westernism, Putin cares about his international image enough to want to avoid defeat.

He cares even more about his power at home.

The Russian people are keen on both the war in Ukraine and Putin: his approval rating is a remarkable 83%.

Gleb Pavlovsky, a former Kremlin consultant, wrote recently that Russians see the war as a “bloody, tense and emotionally engaging” television drama that has little to do with reality but which they want to see continue.

Putin prospers as the drama’s producer and leading man; he cannot rewind the narrative in such a way as to extricate himself.

But the audience’s enthusiasm does not mean it wants to pay to keep watching.

So far the sanctions imposed in response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea have seemed of greater symbolic than economic importance, and this plays to Putin’s strengths.

In Russia he controls the symbols.

But serious economic sanctions of the sort to which the EU seems to have inched closer could do him genuine harm, given the already stagnant economy.

If concern along those lines led to Putin’s efforts on the international stage, though, it does not seem to have changed the situation in eastern Ukraine, or the show being offered to Russian television audiences.

The rebels are still using ground-to-air missiles; they brought down two Su-25s on July 23rd, though they did not use BUKs to do so.

Mr Poroshenko says that weaponry is still rolling over the border to the rebel forces (which he wants the West to designate as terrorists, saying it would be “an important gesture of solidarity”).

American intelligence sources say their analysis, too, points towards continuing supply from Russia.

One explanation for the lack of change could be that Putin does not believe that Europe will act decisively.

The evidence of history seems to be on his side.

Though on July 22nd the council of ministers sent a stronger message than it had before, Europe retains a deep ambivalence about inflicting real economic pain on Russia.

In a newspaper article on July 20th David Cameron, Britain’s prime minister, told fellow European leaders: “It is time to make our power, influence and resources count. Our economies are strong and growing in strength. And yet we sometimes behave as if we need Russia more than Russia needs us…”

They—including Britain, fearful of damage to the City of London—could well continue so to behave.

The most obvious evidence of this is France’s determination to go through with the sale of the first of two Mistral-class helicopter carriers to Russia.

Other nations have demanded the contract be halted, but President François Hollande fears that reneging would endanger shipbuilding jobs at the Saint-Nazaire dockyard, incur stiff financial penalties, leave France with expensive ships it has no use for and damage its reputation for dependability among other countries thinking about entering into arms contracts with it.

That said, sticking with the deal also poses risks to France’s reputation—and to its military equipment makers.

The NATO country which is currently investing most in defence is Poland, with a budget of $46 billion.

France is well placed to sell it combat helicopters and other expensive kit.

But François Heisbourg of the Foundation for Strategic Research, a think-tank, points out that Poland, staunchly opposed to Putin’s power play in the Ukraine, is unhappy about the sale of the Mistrals and unlikely to welcome French arms-sales teams in its aftermath.

Mr Hollande this week tried to deflect the pressure by saying that while the Vladivostok would be delivered this autumn as agreed, delivery of the second such ship—the Sevastopol, ironically—it is building for Russia would depend on Putin’s good behavior.

Meanwhile the head of his Socialist party, Jean-Christophe Cambadélis, hit back at British criticism of the deal, noting that many Russian oligarchs had “sought refuge in London”, and added: “this is a false debate led by hypocrites.”

France is demanding that, in any phase-three sanctions, Britain act on Russian financial transfers through the City.

Germany for its part would be expected to contribute by restricting Russia’s access to high technology, especially in the energy sector.

That is more conceivable than it was; German opinion seems to be turning.

“Nobody can blame Germany for not having taken efforts to talk,” says the German foreign minister, Frank-Walter Steinmeier.

“But Russia did not stick to the agreements to the necessary extent.”

The day after the foreign ministers’ meeting Germany’s mass-circulation Bild, unimpressed, ran a headline mocking the EU for its Empoerend Untaetig—outrageous inactivity.

But if this signals a new German toughness, it is a stance that will build up over months or years, not in weeks.

Doubling down

As Europe plays, at best, a long game, Mr Poroshenko is hoping to regain control of the east of his country with a decisive offensive.

Much will depend on his tactics.

Ukrainian forces have been making liberal use of air strikes and Grad rockets as they move toward Donetsk.

On July 18th 16 civilians were killed in shelling; on July 21st Ukrainian Grad rockets killed four civilians south of Donetsk airport.

“Do I look like a terrorist?” asked Galina Afrena, a woman of 60, as she surveyed the damage wearing a leopard-print dress and carrying a jar of homemade fruit juice.

The Ukrainians say they are under strict orders not to use artillery or air strikes on Donetsk, a city of nearly a million people.

If those orders are followed, it will mark a significant change.

It is natural to expect an enormity to be a turning point.

There is a depressing chance, though, that MH17 will remain an unfathomable aberration.

Ukraine, the rebels and Russia show every sign of eschewing any opportunity it might offer for reflection and reconciliation.

The incompatibility of their interests has only been thrown into sharper relief.

No comments:

Post a Comment