Why NATO is such a thorn in Russia's side

By Diana Magnay

The first American troops arrive at the airport in Swidwin, Poland on April 23, 2014, after Washington said it was sending a force of 600 to the Baltic states as the crisis over Ukraine deepens.

In a telephone call Monday between Russia's Defense Minister General Sergei Shoigu and the U.S. Secretary of Defence Chuck Hagel, Shoigu described the activity of U.S. and NATO troops near Russia's border as "unprecedented."

According to the official Russian version of the call, his American counterpart assured him the alliance did not have "provocative or expansionist" intentions -- and that Russia should know this.

But it hardly seems to matter how often NATO makes these assurances. The Kremlin will never trust them. Fear of the Western military alliance's steady march east is deep-rooted. It strikes at the very heart of Russia's national sense of security, a relic of Cold War enmity which has seeped down to post-Soviet generations.

Ilya Saraev is a 15-year-old pupil at the First Moscow cadet school in Moscow. He thinks long and hard when I ask him about NATO. "I think NATO might be a friend to Russia but there's one point I don't understand: Why it needs to approach the border with Russia more and more," he says.

Cadet school is an education in patriotism, like something from a bygone era. Besides the regular classes, there are lessons in ballroom dancing. Teenage cadets proudly leading local beauties through the waltz while outside their classmates rehearse the goosestep.

After the takeover of Crimea, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry accused Russia of behaving in a 19th century fashion in the 21st century. In some ways it's an epithet that seems to ring true here. The children are immaculately mannered and thoughtful. They write to their fellow cadets in Crimea. They say they feel sad there's this tension between brother nations -- Russia and Ukraine.

"People still don't realize that war means despair and grief," says 16-year-old Vlad Voinakov. "They can't find a compromise because people's interests become involved and that's where the problem lies."

Russia and NATO have never been able to find much of a compromise. Russia's repeated stance is that after German reunification, promises were made that NATO would never expand eastward -- and were promptly broken. NATO says this is simply not true. "No such pledge was made, and no evidence to back up Russia's claims has ever been produced," the alliance wrote in an April fact sheet entitled "Russia's accusations -- setting the record straight."

NATO says it has tried hard to make Russia a "privileged partner." It has worked together with Russia on a range of issues from counter-terrorism and counter-narcotics to submarine rescue and emergency planning. NATO says that fundamentally Russia's anti-NATO rhetoric is an attempt to "divert attention away from its actions" in Ukraine. Now all cooperation is off the table.

"From the Russian side, that NATO-Russian cooperation was just a camouflage," says Vladimir Batyuk of Russian think tank, the Institute of USA and Canada Studies. "After the Cold War Russia tried several times to become a member and the Americans always said, 'it's not going to happen.'" He quotes Lord Ismay, NATO's first Secretary General, on the object of NATO's existence: "To keep the Russians out, the Americans in and the Germans down."

Russian President Vladimir Putin declared at his annual direct call with the Russian people that part of his reasoning for annexing Crimea was to protect Sevastopol, home of Russia's Black Sea fleet, from ever falling into NATO's hands. "If we don't do anything, Ukraine will be drawn into NATO sometime in the future. We'll be told: "This doesn't concern you," and NATO ships will dock in Sevastopol, the city of Russia's naval glory," he said.

Ukraine's Prime Minister Arseniy Yetsenyuk has said Ukrainian accession to NATO is not a priority. The nation is currently in such a state of disarray that NATO membership seems unimaginable. But a membership action plan was discussed for both Ukraine and Georgia at the Bucharest Summit in 2008. It was put on hold. But Putin does not forget.

"Ever since (former Ukraine President Viktor) Yanukovych fled his country and a pro-Western government took power in his country, of course this is something [Putin] couldn't stop thinking about," says Masha Lipman of the Carnegie Moscow Center. "So for him, to prevent Ukraine from becoming part of the western orbit if not of NATO, was something he absolutely cannot afford."

This is why the rotation of 600 U.S. troops, small as it is, through the Baltic states and Poland for joint-training exercises is such an affront for Russia. This is why it is perhaps not strictly fair to accuse Russia of just engaging in propaganda when it declares its mistrust of NATO.

Batyuk says he feels that the general public's attitude to the alliance has worsened since the end of the Cold War. Then, people were able to dismiss the Kremlin's line towards NATO as Soviet propaganda, he says. Now it's different. "A store of unsuccessful mishaps in relations between Russia and the West after the end of the Cold War has contributed to a rise in suspicions on the Russian side to Western policy in general and NATO in particular."

That's one of the reasons Putin's popularity has soared since the annexation of Crimea. There is a feeling among the general public that, at last, Russia is standing up for its rights in the post-Soviet space where it has sat maligned for decades. Much as the Kremlin likes to nurture that narrative, it is also easy to see why it resonates with the Russian public.

Associated Press: 1. May 2014

NATO official says Russia now an adversary

Alexander Vershbow, the deputy secretary-general of NATO, says NATO should "begin to view Russia no longer as a partner but as more of an adversary than a partner."

After two decades of trying to build a partnership with Russia, the NATO alliance now feels compelled to start treating Moscow as an adversary, the second-ranking official of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization said Thursday.

"Clearly the Russians have declared NATO as an adversary, so we have to begin to view Russia no longer as a partner but as more of an adversary than a partner," said Alexander Vershbow, the deputy secretary-general of NATO.

In a question-and-answer session with a small group of reporters, Vershbow said Russia's annexation of Crimea and its apparent manipulation of unrest in eastern Ukraine have fundamentally changed the NATO-Russia relationship.

"In central Europe, clearly we have two different visions of what European security should be like," Vershbow, a former U.S. diplomat and former Pentagon official, said. "We still would defend the sovereignty and freedom of choice of Russia's neighbors, and Russia clearly is trying to re-impose hegemony and limit their sovereignty under the guise of a defense of the Russian world."

In April, NATO suspended all "practical civilian and military cooperation" with Russia, although Russia has maintained its diplomatic mission to NATO, which was established in 1998.

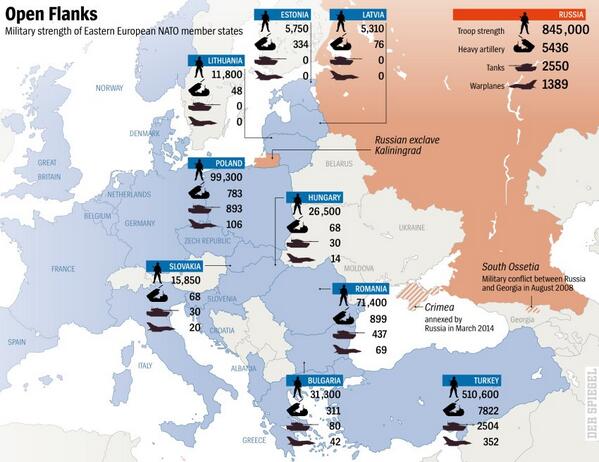

Vershbow said NATO, created 65 years ago as a bulwark against the former Soviet Union, is considering new defensive measures aimed at deterring Russia from any aggression against NATO members along its border, such as the Baltic states that were once part of the Soviet Union, Vershbow said.

"We want to be sure that we can come to the aid of these countries if there were any, even indirect, threat very quickly before any facts on the ground can be established," he said.

To do that, NATO members will have to shorten the response time of its forces, he said.

Vershbow, a former U.S. ambassador to NATO, said that among possible moves by NATO is deployment of more substantial numbers of allied combat forces to Eastern Europe, either permanently or on a rotational basis.

For the time being, he said, such defensive measures would be taken without violating the political pledge NATO made in 1997 when it established a new relationship with Moscow on terms aimed at offsetting Russian anger at the expansion of NATO to include Poland and other nations on Russia's periphery. At the time, NATO said it would not station nuclear weapons or substantial numbers of combat troops on the territory of those new members. For its part, Moscow pledged to respect the territorial integrity of other states.

Vershbow argued that Russia has violated its part of that agreement by its actions in Ukraine, and thus, "we would be within our rights now" to set aside the 1997 commitment by permanently stationing substantial numbers of combat troops in Poland or other NATO member nations in Eastern Europe. He said that question will be considered by leaders of NATO nations over the summer.

Reuters: 1. May 2014

NATO says seeking closer ties with Georgia as Ukraine crisis mounts

NATO said on Thursday it was looking at ways to bring Georgia "even closer" to the military alliance, in the latest signal of support for the former Soviet republic as tension mounts between Russia and the West over Ukraine.

James Appathurai, NATO Special Representative for the Caucasus, said he would not let Russia's words or actions influence the final decision on whether to make Georgia a full member, a likely reference to Moscow's opposition to the move.

The statement came less than a week after France and Germany assured Georgia that a deal bringing it closer to the European Union would be sealed soon.

Relations between Georgia and Russia were badly strained by a five-day war in 2008, when Moscow's forces drove deep into the small Caucasus country.

That war was partly a result of Tbilisi's long-running drive to move closer to the EU and join NATO, an alliance of 28 nations that has been the core of European defense for more than 60 years.

Despite attempts by Moscow and Tbilisi to improve ties after a change of government in Georgia in 2012, they have still not restored diplomatic relations and Russia annexation of Ukraine's Crimea region in March revived Georgian security concerns.

"What Russia says or does will not influence our decision ... We will judge Georgia on Georgia's merits and regardless of what's happening elsewhere and regardless of comments from the Kremlin or elsewhere," Appathurai told a news conference in Georgia's capital Tbilisi.

Georgian military personnel and vehicles parade through central Tbilisi

He said NATO was still committed to Georgia become a member. "We are now looking, of course, at next steps, at bringing Georgia even closer to NATO and to meeting its goals," he said.

A NATO summit in September is scheduled to discuss the position of four potential members - Georgia and the former Yugoslav republics of Montenegro, Macedonia and Bosnia.

Appathurai praised Georgia's progress. "I can tell you that overall, this assessment in NATO is positive. Year after year Georgia continues to improve and that's because of the hard work done in this country," Appathurai said.

Georgia has strategic importance because it is on the route of pipelines which carry oil and gas from the landlocked Caspian Sea - seen by many countries as an alternative to Russian energy - to world markets.

It plans to sign a trade deal with the European Union in June - the same kind of pact whose rejection by Ukraine in November touched off the biggest East-West crisis since the Cold War.

Georgia has some 1,560 troops in Afghanistan, making the country the largest non-NATO contributor to the mission

The United States and the EU have stepped up support for other former Soviet republics in a tug-of-war with Moscow.

No comments:

Post a Comment