Ukraine’s military wasn’t up to the task of fighting off pro-Russian separatists itself. So ordinary citizens are picking up the slack.

Harkiv, UKRAINE -- The war in eastern Ukraine is often cast as a conflict between the Ukrainian army and Russian civilians. In fact, though, it's just the other way around: Well-trained troops from Russia are fighting Ukrainian civilians who lack prior military experience. "Little green men" from Russia appeared in Crimea in advance of the March secession referendum, and battle-hardened fighters from Chechnya arrived in eastern Ukraine as unrest began there in April, while tens of thousands of Russian regular troops amassed on Russia's border with Ukraine. But since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Ukraine never got around to building a proper army of its own. Now civilians are taking matters into their own hands.

When the first shots were fired, the Ukrainian armed forces found themselves hamstrung. Endemic corruption and chaotic bureaucracy had crippled the armed forces. Few weapons were in a working state. A private company had rented twenty-five military helicopters from the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense, who leased them to earn money. That left only 10 working choppers for military needs. The country's leaders had never really planned to use their army other than in several UN peacekeeping missions, which are usually planned well in advance.

As the war dragged on, it soon became obvious that Ukraine's deeply entrenched culture of corruption was preventing funds from getting to where they were needed. When the military demanded body armor for the troops, the government responded by launching a three-month tender process.

Ordinary citizens, incensed by the news of Ukrainian soldiers going into combat without any protection, decided to take matters into their own hands.

Ordinary citizens, incensed by the news of Ukrainian soldiers going into combat without any protection, decided to take matters into their own hands. Almost overnight, activist groups sprang up to help "self-assigned" military units.

Organizing through social media, groups with names like "Help the Army" and "SOS Army" began taking over responsibility for managing and delivering supplies to the armed forces. The organizers of these efforts used websites like PayPal and WebMoney to collect donations from Ukrainians at home and abroad, then used the money to purchase materiel ranging from expensive thermal imaging devices to homemade jams and pickles.

Volunteers are pitching in other ways, too. Members of the far-flung Ukrainian diaspora (including seasonal workers in Germany and Italy) have been sending in money and used Western military uniforms as well as equipment like bulletproof vests and binoculars. Priests organize fundraisers. Prison inmates have been contributing voluntary overtime (at least according to the organizing activists) to manufacture barbed wire for the front lines. In Kharkiv, SOS Army has helped the army clean and repair weapons and readied more than 90 old armored personnel carriers for combat, always buying spare parts themselves. "We feel like every Ukrainian now feels obligated to send something to the front line," says Yuri Kasyanov, a coordinator for SOS Army.

Activists are also organizing transportation. Every day they drive civilian cars between Kharkiv and frontline checkpoints, on roads where sniper fire can ring out at any moment, to deliver supplies to military units (which themselves often consist largely of volunteers). While some initiatives have been set up by Ukrainian right-wing groups, the majority of the volunteers are ordinary people, though the Russians have over-emphasized the presence of such groups in their media campaign. "There were moments when our fighters had absolutely no food or water," says Yelena (who only gave her first name because she's been receiving threats from pro-Russian forces). "We've solved this problem for the moment, but they still lack such everyday things as tents, sleeping bags, and even toothpaste."

Needless to say, all of this goes against accepted bureaucratic procedure. Officially, the army commanding officer cannot ask for help or equipment from civilian sectors, and would probably face a court martial for doing so. Given the inability of the army to solve these problems on its own, however, they have few other options.

Perhaps most remarkably, accounts for everything provided by the volunteers -- including invoices, receipts, and delivery confirmations from military commanders -- is accessible online. Every week the groups publish a full inventory of what they've supplied to each unit as well as describing items or services that are still needed.

In this way, these new organizations offer a highly visible alternative to corrupt government institutions. Their transparency helps to attract funds by building trust. Those who donate can track how their money is being allocated in real time -- and feel a sense of satisfaction when they see the results.

Citizens are now increasingly saying that they want their actual government and military institutions to function as well as the forces mobilized by citizens.

Citizens are now increasingly saying that they want their actual government and military institutions to function as well as the forces mobilized by citizens. There has been a recent campaign to put details of all government tenders online.

Ordinary citizens donations are often deliverd to soldiers rigth on the front line.

The military has been scrambling to catch up. On June 20 the Ministry of Defense announced several new tenders for food and body armor for the army. Parliamentarian and ex-defense minister Oleksander Kuzmuk dismissed the move as too little, too late. But the culture of transparency is slowly catching on, and the Ministry of Defense has begun putting more information online.

Having discovered the virtues of openness, many of these volunteer logisticians are increasingly criticizing the army for maintaining closed information policies that are antagonizing would-be supporters. "Apparently ignorant of the existence of Google Maps, GPS, and satellite imaging, the Ukrainian army is calling journalists ‘spies,' and is even preventing them from taking pictures of checkpoints without special permission," wrote SOS Army coordinator Yuri Kasyanov in a Facebook post. "It's not surprising we're losing the information war with Russia."

While he acknowledges a need for some degree of secrecy for military operations, Kasyanov is concerned that if journalists are not allowed near any of the conflict areas, Russia dominates the media agenda by distributing disinformation while quashing any alternative views. On several occasions Russian websites have been caught appropriating digitally manipulated images from other conflicts and claiming that they're occurring in Ukraine.

Local hospitals in eastern Ukraine are poorly equipped, having been neglected for decades. When the first wounded and dead started arriving, activists assumed roles usually assigned to military medical services or government departments of veteran affairs. While doctors volunteer for operating rooms, others set up blood drives, collect medications and medical equipment, organize body identification, and offer support networks to families. (Some volunteers concentrate on obtaining products that aren't available in Ukraine, such as Celoxdressings and powders that prevent bleeding.) Once again, detailed accounts of these activities are also documented online, including lists of blood donors who are ready to make donations at a moment's notice.

As more and more fighters head off to the front lines, activists have also created a hotline for families and refugees to coordinate aid to the armed forces and to connect families with their loved ones. Those who operate the hotline say that, in addition to legitimate inquiries, they also regularly receive death threats from callers in Russia.

Given these efforts to attack the morale of Ukrainian volunteers, it's only logical that some civilian activists are also engaging in activities that might be classified in some quarters as "psychological operations."

Given these efforts to attack the morale of Ukrainian volunteers, it's only logical that some civilian activists are also engaging in activities that might be classified in some quarters as "psychological operations." The military's supporters put up banners near the combat zones with slogans ("Kharkiv and Donetsk are the heart of Ukraine") to boost military morale. Another project, "Draw Peace for a Soldier," sends children's drawings to soldiers. It's all been done in a total end run around the dysfunctional Ministry of Defense.

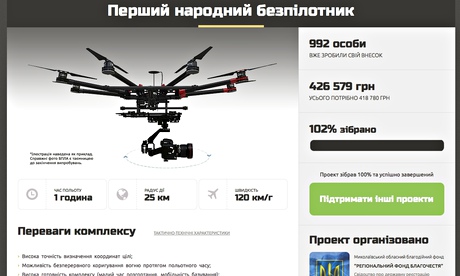

Volunteers recently added an even more surprising job to their expanding portfolio: intelligence gathering. The website StopTerror.UA invites ordinary Ukrainians to send in texts and emails with useful particulars (such as troop movements, roadblocks, illegal building seizures, and even the unauthorized dismantling of state symbols), which it then posts in real time on a map. The same group has also started a collection to fund the first intelligence-gathering drone in Ukrainian history.

Activists are hoping that this experience of grassroots participation in the war effort will promote a new civic spirit and give Ukrainians the strength to fight corruption on all levels. The army, historically, has been one of the institutions most resistant to reform, so reformers are hoping that the current wave of volunteer activism will have a big demonstration effect. Tanya Bednyak, a small business owner from Kharkiv who leads Help the Army, puts it this way: "War now is like an extremely painful but necessary surgical procedure that in the long run will revitalize the country and its dysfunctional institutions."

No comments:

Post a Comment