By: Olivia Ward

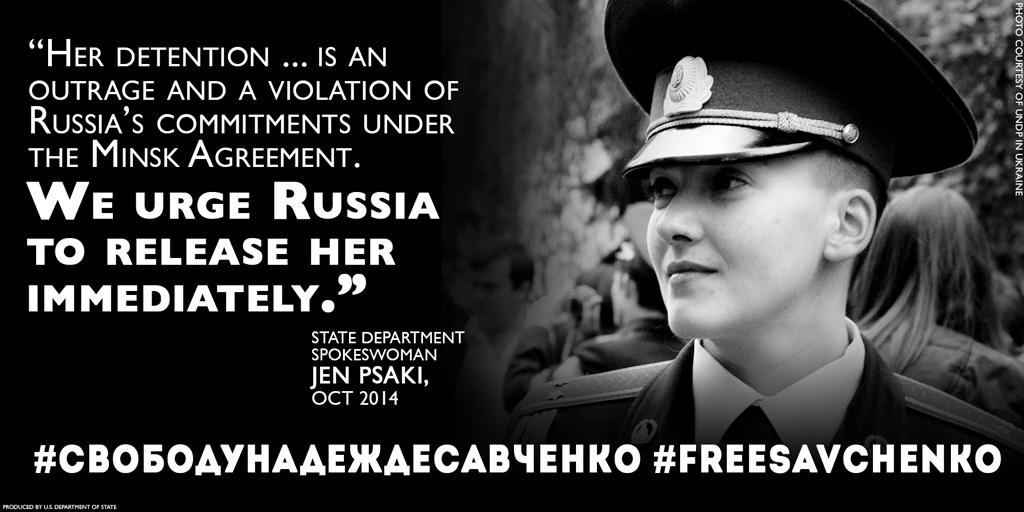

Nadiya Savchenko, a fashion designer turned air force fighter who is now languishing in a Russian jail, has shattered stereotypes and become a symbol of Ukraine’s battle with its neighbour.

After a month on hunger strike in a Russian prison cell, Nadiya Savchenko is staring death in the face.

But the Ukrainian fashion designer turned front-line fighter is meeting it — and Moscow’s ire — with true grit that has made her Ukraine’s “Joan of Arc,” even as Russia denounces her as a “Daughter of the Devil” and charges her as an accomplice to the murder of two journalists during fighting in eastern Ukraine .

“I have given my word,” she wrote in a defiant letter from a Moscow jail , released Monday by her lawyer. “Until the day I return to Ukraine or until the last day of my life in Russia … I will not back down.”

This week, Kyiv’s parliament called on the leaders of Russia, Germany and France to help free her.

Since her capture by pro-Russian separatists in the combat zone last July, Savchenko has become the heroine of an ongoing drama that has reached a global audience.

Now 33, she rose from impoverished student to graduate of Ukraine’s prestigious Air Force Academy, newly named MP and member of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe. She has shattered sexist stereotypes to become a poster girl for Ukraine’s battle with its giant neighbour, which has seized the Crimean Peninsula and is now eyeing Ukraine’s turbulent eastern region.

But Savchenko is also at the centre of a deeply polarized Cold War redux, and her fate goes beyond the borders of Russia and Ukraine.

Her case is “absolutely political,” said Savchenko’s Russian lawyer, Mark Feygin, who defended members of punk group Pussy Riot . “It can be resolved only through political means because legal avenues are not working.”

He believes Savchenko will be top of mind at a peace summit on the Ukraine conflict in Astana, Kazakhstan, later this month.

Supporters hope it’s not too late. Now in solitary confinement in Moscow, Savchenko is surviving on sips of water, with sporadic infusions of glucose through an intravenous drip. She agreed to the treatment to avoid the “torture” of force feeding, said her sister Vera, in an interview through a translator.

Close friends, the sisters were together before Nadiya was seized on July 17 during the rescue of some wounded Ukrainian soldiers near the front line. Nadiya was on a training mission in eastern Ukraine after taking a leave from the army, which refused to send female soldiers into combat. Vera had volunteered to drive her to the front, and then joined in the rescue when ambulances “were afraid to come to the area.”

While transporting injured soldiers during a raging battle, Vera said, she lost contact with Nadiya and feared she was dead. But the next day, Nadiya’s cellphone was answered “by a man from the separatist movement who screamed and yelled curses and threats.”

Believing her sister was alive, Vera launched talks with the separatists for a prisoner swap. But the effort failed, and she later learned from a letter written from jail that Nadiya had been transported over the border to Voronezh, in southern Russia: “They put a balaclava over her head and changed cars six times.”

Russian authorities insist that Savchenko sneaked over the border illegally, but she and her family contend she was kidnapped. “They didn’t expect that this case would cause such a scandal,” Feygin said.

Ukrainian pilot Nadiya Savchenko (in the cell) on kangaroo trial in Russia.

Savchenko was questioned by Russian officials and charged with responsibility for the mortar attack that killed Igor Kornelyuk and Anton Voloshin , two Russian TV journalists who were on a reporting trip in the area. She has consistently denied the charge, and her lawyers say it was “impossible” because she was captured well before the two died. “The Russian case is empty,” Feygin maintains.

Savchenko is no stranger to controversy.

Growing up in impoverished Ukraine — her father was a mechanical engineer and her mother a seamstress — young Nadiya wanted to become a journalist, but had to drop out of Kyiv University because of lack of money. Instead she graduated from a less expensive fashion design college.

But childhood holiday trips to Crimea had sparked a love of flying, and she hankered to become a jet pilot. With the Air Force Academy closed to women in the early 2000s, she joined the low-paying Ukrainian army.

After an assignment in Iraq, she finally got her wish, graduating as one of only two women newly admitted to the air academy. When the revolution dubbed “Euromaidan” broke out in 2013, she joined its self-defence squad, breaking a taboo against women playing active roles in fighting the security forces. And when the ouster of Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych led to Russia’s seizure of Crimea and backing for pro-Russian separatists in eastern Ukraine, she rejected the army’s stand on keeping women away from the front.

Savchenko is the most famous symbol of Ukraine’s female fighters. But she is one of dozens of women who have thrown off the restraints of a male-dominated society since the Euromaidan movement began.

“She is a symbol is some ways, but not really for feminism,” said sociologist Tamara Martsenyuk of the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, now a visiting scholarat the University of Toronto. “She could be perceived as a woman suffering because of Ukraine’s relations with Russia.”

Women have been marginalized in the military and in politics, she points out. Yulia Tymoshenko , whose party put Savchenko on its electoral list, is typical of the image of a successful Ukrainian woman, Martsenyuk adds: “She’s wealthy, beautiful, married, has children and is also a politician.” In the military, women have low-status, low-paying support jobs and little hope of advancement. And in marriage, working women “still come home and cook the dinner.”

If Savchenko is released, she could be on the front line of change. But as the hunger strike continues, her fate is uncertain.

“She rejects all demands and pleas for her to end her hunger strike and says she will fast to the bitter end,” Russian human rights campaigner Anna Karetnikova told Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. “She’s chosen her path and doesn’t want to hear any advice.”

No comments:

Post a Comment